How Is Art Affected by the Holocaust in the Novel Maus

T o mark the 25th anniversary of the publication of Maus, the but comic ever to win a Pulitzer prize, its creator, Art Spiegelman, brings yous a big, fat book called MetaMaus. How to draw this extravaganza? In essence, it's a nerd'southward guide to Maus: sprawling and definitive. There are transcripts of Spiegelman'due south interviews with his father, Vladek, a Polish Jew who survived Auschwitz, and whose story Maus tells; a long and exhaustive interview with Art, plus shorter ones with his wife, Françoise, and his children, Nadja and Dash; early on draughts of Maus artwork; and copious examples of his many and various influences, from Donald Duck to Primo Levi. Should all this still not be plenty, attached to its embrace is a hyperlinked DVD, containing a Maus audio archive. If yous like comics, are thinking of entering Mastermind whatsoever fourth dimension soon and are stuck for a subject area, here is the answer to your prayers.

My favourite part of the book, though, is the department in which Spiegelman reproduces the rejection letters he received when his agent, Jonathan Silverman, offset sent Maus out to publishers. Oh dear. This is embarrassing. Behold New York's literary gustation-makers acting similar a agglomeration of cowardy custards. "Cheers for letting me see Maus," says Hilary Hinzmann, of Henry Holt. "The idea behind information technology is brilliant, but information technology never, for me, quite gets on track." Gerald Howard, at Penguin, is a little more upwards front, merely however, he won't quite take all the blame for turning it down: "In office, my passing has to do with the natural nervousness i has in publishing something so very new and perchance (to some people) off-putting. Just more than crucially I don't think Maus is a completely successful work, in that it seems in some way conventional."

At St Martin's Press, Bob Miller admits that he establish the book "quite affecting" (hell, he fifty-fifty managed to read right to the cease). But what on earth would he tell the sales section? "I can't run across how to advance the affair into bookstores." Fifty-fifty the great Robert Gottlieb of Knopf, publisher of Catch-22, doesn't get information technology. "It is clever and funny," he writes. "Only right now, nosotros are publishing several comic strip/cartoon blazon books and I think it is too soon to accept on another 1."

In his ramshackle SoHo studio – a sort of comics library with a membership of just one, it consists of a dingy bath, a kitchenette, a cartoon lath, the odd dusty plant and about eight million quietly groaning books – Spiegelman lights yet another cigarette. (You would be more likely to see a giraffe wandering down Mercer Street than a New Yorker who smokes with quite his dedication.) He then gives himself over to crowing delightedly. "I've met a number of editors over the years," he says, eyes rolling. "And all of them claim to have discovered Maus, when all they really have the right to claim is that they rejected it. One of them [the aforementioned Hilary Hinzmann] actually said it was also much similar a sitcom." However, no difficult feelings. "If I'd heard the brusk-course clarification of it, I might have put information technology in the out-tray, likewise. It's a comic book! About the Holocaust! Oh, groovy. And there are mice in it! [for the uninitiated, Spiegelman's Jews are mice, his Nazis are cats, his Poles are pigs and his Americans are dogs].

'You can't blame them. There was a bookstore in my neighbourhood that kept Maus on its table of new releases for years. So, finally, I introduced myself. 'This is and then, fantastic,' I said. 'The way yous keep my volume hither.' But the manager, who was actually grumpy, said, 'It'due south but because I tin can never figure out where to put the damn affair!'" He sniggers. "I guess that would sit badly with a publisher. I mean… exercise you put it near Garfield, or what?"

The book, which was finally published by Pantheon in the Us, was a New York Times bestseller, has been translated into 18 languages and has won numerous prizes. "It has become canonical," says Spiegelman (simulated modesty – or any other kind of modesty, in fact – is non really his thing). "There's no way out of information technology: if I were a blues musician, it would play in car commercials. It has entered the culture in ways that I never could have predicted." Its success, however, took him by surprise at first – and it led him towards a kind of nervous breakdown. For a while, he didn't know if he would be able to produce the 2nd volume (Maus Two eventually came out in 1991). "I didn't know how to continue through the gates of Auschwitz," he says in MetaMaus (the first book ends equally Vladek and Art's mother, Anja, are betrayed by the smuggler who is supposed to evangelize them from German-occupied Poland to safety in Hungary). "I retrieve that the shock of being celebrated, rewarded for depicting and then much death, gave me the bends..."

Even after Maus II was consummate, it felt, sometimes, like a kind of expletive. "Maus is an ongoing problem for me, and for other comic artists," he says, at present. "It was a paradigm-shifting book. Afterwards, comics were no longer jejune adventures for kids – apathetic, blah, blah – and and so every new comic book must be compared to it. Mass culture is so fucking stupid. It says that what's important well-nigh Maus is that information technology'southward nigh the Holocaust. Certain, Maus cut through a lot. Of a sudden, you could write nigh really serious things in a comic. Simply in the caricature version, that ended upwards every bit pregnant that things [ever] had to be ponderous." He flicks his lighter yet again, leaning prayerfully towards its flame. "I suppose you could say that the residual of my life has been spent figuring out how to walk around it."

The shock of Maus, and the source of its bang-up and enduring power, lies in Spiegelman's absolute refusal to sentimentalise or sanctify the Survivor, in this case, his father. During the war, Vladek lost his vi-year-old son, Richieu, poisoned by the aunt to whom his parents had sent him for safety-keeping, in order that he might avoid the gas chambers; he lost almost of his extended family, and he endured months of the most appalling fright and hardship in Auschwitz-Birkenau and, later on, Dachau. But unimaginable suffering, Spiegelman wants united states of america to sympathize, doesn't brand a person better; it only makes them suffer.

For this reason, he sets the European role of Vladek's story against his later life in Queens – Vladek, Anja and Art, who was born later the war, emigrated to the Us in 1951 – where Fine art, with whom he has a strained, fractious relationship, painstakingly interviews him, in the promise of turning his tale into his outset book (Anja committed suicide in 1968). Vladek, we grasp immediately, has grown into a thoroughly exasperating quondam human being: stubborn, parsimonious, bullying. He is guilty of casual racism (he refers to black people as "shvartsers" and expects them to steal from him). He treats his despairing 2nd wife, Mala, some other Holocaust survivor, like a retainer. He considers his but surviving son, who cannot mend a roof and has failed spectacularly to go a physician or a dentist, to be a failure.

Art, at to the lowest degree as he tells it in his book, tin barely stand to be in the same room as him for more than 5 minutes – unless, of course, he is talking near the war. "This is the oddness of it," he says. "Auschwitz became for united states a safe place: a place where he could talk and I would listen."

Vladek died in 1982. Does Spiegelman miss him? Just for a beat, he falls silent, the only time in our 90-minute chat this happens (he talks even faster than he smokes). "I can't quite answer that," he says. "Non exactly. I don't believe that another 10 chances would have gotten me at that place [reconciled us]. On the other hand, I could be more tolerant now. I miss my mother. Simply my father is always a trouble. Parents are these weird creatures. They don't accept scale. They're well-nigh 100 feet high when you see them from downward there on the rug, and no matter what y'all practice, no matter if you have an incredibly useful shrink, as I did, they pop back up to that size thanks to some early wiring in your brain."

Did writing Maus, in which his begetter is depicted with cool remorselessness, feel similar an act of expose? "Having a writer in the family unit is to accept a traitor in information technology; it's basic to the projection. But… looking back, I really don't remember going to enquire my pop if he would play ball. I've tried, only I simply can't conjure those moments. He brought me paper, it had adverts for winter coats on i side of it – this was when he was working in the rag merchandise – only you can hardly build a fun childhood effectually $.25 of paper with winter coats on them. I just found him… maddening."

In Maus, however, Vladek's rumbling belligerence has another role, also: it is another way of disarming those – we might call them the "never again" brigade – who would depict piece of cake morals from the book. Spiegelman was determined that Maus be "exempt" from certain things. "It's not a book nearly Israel," he says, with a grinning. "Because, fortunately, my parents turned right and not left when they left Poland [the couple were miraculously reunited in Sosnowiec some weeks later on the state of war concluded]. And it'due south not a happy ending story similar Schindler'due south List, where all those nice former people stand effectually at the cease. I accept a friend who says those old people should really have appeared in every scene, shouting at all those handsome moving-picture show actors, 'Pastrami? You think we had pastrami?'" He loathes "those standard Holocaust tropes".

As he sketched – completing the projection took him some 13 years in all – he had the odd merely thrilling feeling that he was working on something that was both "enormous" and bracingly containable. "The mouse metaphor allowed me to universalise, to draw something that was too profane to depict in a more than realistic way, simply my father's personal trajectory was also relatively small… I mean, I read about Treblinka, where there were no survivors [come across footnote]. But I could think: to hell with Treblinka, my parents weren't there!"

He knew his animate being metaphors would suspension downwards in the end (how, for instance, to evidence that Anja, hiding in a cellar, was afraid of rats?). Just this suited him simply fine. A Jew, Jean-Paul Sartre said, is someone other people telephone call a Jew. His scheme emphasised just how dumb it was of the Nazis – or anyone – to lump humanity into arbitrary groups.

The book was acclaimed, merely it had its critics, too. "When I first talked well-nigh it [in public], there were just these shouting matches with the audience. I couldn't say anything about State of israel, about how nation states are not a satisfactory answer; people would go berserk." Though his Jewishness was hardly a secret – "or not to anyone who could read my final name" – Maus made him overtly Jewish to the earth, and this has been a complicated business considering, as he puts it in MetaMaus: "The but parts of Jewishness I tin can embrace easily are the parts that are unembraceable. In other words, I am happy being a rootless cosmopolitan, alienated in virtually environments that I fall into. And I'thousand proud of being somebody who synthesised different kinds of culture – it is a fundamental aspect of the diaspora Jew. I'one thousand uneasy with the notion of the Jew as a fighting machine, the two-fisted Israeli." Do his enemies accuse him of existence self-hating? "Oh, sure. Commonly, I just fall back on Woody Allen and insist that information technology's non that I'm a self-antisocial Jew – I simply hate myself. Or, even better… a friend of mine was attacked by Alan Dershowitz [the controversial defence force lawyer] for being a self-hating Jew and my friend told him, 'I don't hate myself. I just hate you!'" He sniggers.

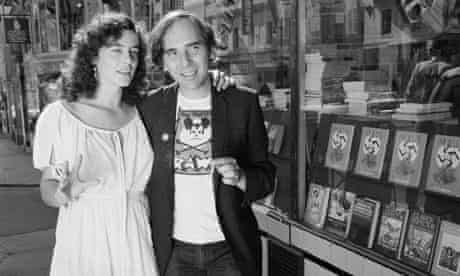

Spiegelman, who was born in Stockholm in 1948, grew upwards in Rego Park, Queens, a devoted reader of Mad magazine. He attended college – the plan was to read philosophy – but did non graduate and, in 1968, suffered a brief but intense nervous breakdown, an episode he periodically refers to in his work. (It was presently after he left infirmary that his mother committed suicide.) Thereafter, he worked in the secret comics scene and – this human relationship lasted for xx years – at Topps chewing gum, where he designed Wacky Packages, a series of collectible stickers. Then, in 1976, he met Françoise Mouly, a French compages educatee. They married and began producing a comic showcase called RAW on the printing printing she had installed in her SoHo loft. It was in RAW, with its crazily erratic publishing schedule (11 issues in well-nigh as many years), that the very first Maus stories appeared. "Our large problem when we did RAW was the business end of things," he says. "We found information technology difficult to get up earlier the banks airtight." In Maus, Mouly is depicted as at-home and wise. "Yeah, in the volume she functions every bit a stabilising rod that keeps the nuclear establish from exploding, and she definitely has that role in my life. But she has her own madnesses. She'due south nuts."

In 1993, Tina Brown, so editor of the New Yorker, published a controversial cover by Spiegelman, ane of her new contributing editors, of a Hasidic Jew kissing a black adult female. Soon subsequently, apparently inspired past what she saw at the RAW offices, she brought Mouly to the magazine as art editor, a position she notwithstanding holds (Mouly, in turn, brought with her neat RAW cartoonists such equally Charles Burns and Chris Ware).

Spiegelman, however, resigned from the magazine soon after the eleven September attacks (he and Mouly created the New Yorker's remarkable Twin Towers encompass – a blackness rectangle in which the towers are picked out in silhouette in a very slightly darker shade – together). "Information technology was fun for a while [at the New Yorker], simply too much of my brain was rented out, and it was frightening, having to render to quotidian covers after nine/11. You lot know: 'Segways are hot! Practise you have a cover near Segways?' It wasn't interesting."

Simply he had besides go obsessed with the ideas that eventually became his book In the Shadow of No Towers, strips that the New Yorker would not publish (it drew some uneasy parallels between the horror suffered by his parents and his ain experiences on that day). "The uncanny thing about eleven September is that I felt like a rooted cosmopolitan for a moment. It happened 10 blocks from my house and I felt an incredible affection for New York considering it seemed and so vulnerable, and it had felt so eternal and inevitable and bonecrushing. I can find that feeling again, even now, just the damn thing got hijacked so chop-chop. It became an regular army recruitment poster inside 2 weeks. I got used." He is disappointed that the city has elected to build new "arrogant" towers on the site of those that vicious.

He thinks MetaMaus, with its elegant binding, and its varied paper textures, is "ameliorate than it had any right to be – an ceremony book is commonly a kind of Sears catalogue that goes in the garbage five hours later". But is it a last gasp equally well as a full stop? Does he worry that we will soon lose newspaper? He shakes his head, boyishly. "Yes, everybody [in publishing] is panicked, and they aren't thinking clearly. Yes, books have a role that tin can be partially supplanted by a little device. Only there are other things that can only exist experienced from the limitations of paper. Some books want to be petted. The books that have a correct to be books brand use of their bookness. Graphic novels – who knew that term would stick! – continue to do well considering they use their bookness. Comics don't desire to exist sizeless."

He continues to work here, "in the studio that Maus built", on paper and on screen, just also at a log motel in Connecticut, which, to his surprise, he and Françoise similar to visit. "I take absolutely no interest in flora and fauna. 'Christmas' and 'other' are the only two categories of trees in my head. Unless it'south a grizzly bear, I don't give a shit what's walking by. Just this, it turns out, is great, because I can walk, and I tin recall, and I tin can solve bug in a way that I can't in New York." Does this mean that he is at work on – at last – a new long work? Some in the cartoon world snipe that he is starting to look similar a guy with just one slap-up book in him. "Ha! My stock response to that question used to be: one time a philosopher, twice a pervert. Look, I am and then proud of Maus. But my cells have replenished themselves several times since. I remember that, finally, I am at the beginning of trying to effigy a new book out. Maus does [he knocks his duke on the table] well enough that I don't accept to chase every ambulance. I've no need of advances, and so on. That should give me incredible licence." He grins, contrarian to the terminal. "But who am I kidding? I guess I'll always exist nostalgic for the old days."

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/oct/23/art-spiegelman-maus-25th-anniversary

0 Response to "How Is Art Affected by the Holocaust in the Novel Maus"

Post a Comment